This is Part Four in our music lessons from Ocarina of Time. Check out Part One, Part Two and Part Three here!

Even though I’ve already written three whole blogs about the different musical techniques used in Ocarina of Time, there’s so much to talk about and learn from in this soundtrack I felt another blog was necessary (perhaps I have some sort of obsession, I don’t know). We’ve already seen how Koji Kondo used modes, chromatic harmony and different forms to create variety in the music, but there’s something we didn’t look at. Something weird… something unnatural…

… the whole tone scale.

This is a scale many musicians and composers may have heard of, but actually finding practical examples of its use is pretty hard. We find it in Ocarina of Time in the Chamber of the Sages, as well as the cut scenes that show the three goddesses creating Hyrule.

As may be obvious from its name, it is a scale built entirely of tones, a tone being the equivalent distance between C and D, sometimes referred to as a whole step. You could also think of this as two fret’s distance on a guitar. Half this distance, so C to D flat, is a semitone, or half-step. Major and minor scales and the seven modes are all seven notes long, but the whole tone scale is only six. After moving six tones in either direction, you are back where you started.

All the scales and modes you would be familiar with are built out of a specific pattern of tones and semitones, and it is the specific nature of this pattern that gives each scale its own unique sound. But because every step is exactly the same in a whole tone scale, anywhere you begin in the scale sounds exactly the same. There is no difference between intervals anywhere that makes any part of it sound more important, or like it is the centre of the scale. This makes it quite functionally pan-tonal. This means every note is equally important. Every note in the scale could be the centre of the scale, as every position is the same in relation to anywhere else.

A major scale has a semitone between the final note of the scale and the tonic. When you hear the semitone below the tonic, you can feel it wanting to resolve to the tonic (this is why the seventh position of the scale is called the leading note, it leads to the tonic). Minor scales often have the seventh sharpened (it is naturally flat) to create a leading note. The leading note really helps define the tonal centre, because you can hear where it is trying to go. The whole tone scale of course doesn’t have a leading note, as there is no distance of a semitone anywhere, which is one of the reasons the tonic of the scale is ambiguous, another reason it is pan-tonal in nature.

Yet another reason it is tonally ambiguous (if you needed another reason) is that you can’t build major or minor triads anywhere in the scale. Stacking thirds anywhere in the scale can only give you augmented triads, which is a major triad with a sharpened fifth. These work well as a substitute for dominant seventh chords in a perfect cadence, and sound like they are trying to resolve a fifth away. So a G augmented chord sounds like it is trying to resolve to C, for example. But there is no distance of a fifth in a whole tone scale, and any other triad you build is just an augmented chord anyway, so you can’t resolve the cadence. Just to be clear, you can create chords in a whole tone scale which aren’t augmented chords, but augmented chords are the only ones you can build out of stacking thirds on top of each other, like how one would typically build a major or minor triad. Coming up with chords in a whole tone scale does involve some imagination however, and usually complex extensions, clusters and inversions.

So this is why I described it as weird and unnatural earlier. It isn’t exactly dissonant or unpleasant, it’s just… weird. It can make you feel slightly unsettled, because there is no real tonic to settle on. This is why it is a useful scale to build music on when trying to create a mysterious sound. The Chamber of the Sages is certainly a mysterious place, so using whole tone music is a great way of establishing the atmosphere.

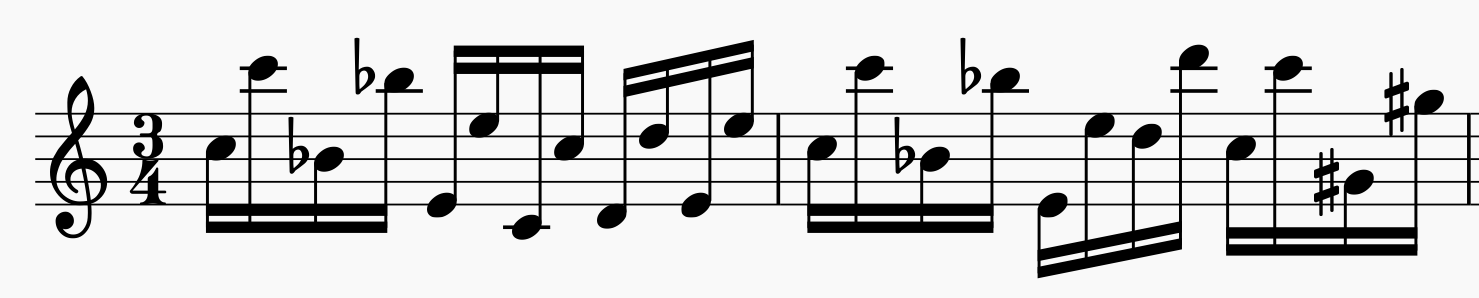

Let’s have a look at the music. A rather spooky and disjointed vocal melody is supported by a main theme that constantly jumps around in octaves, like this:

The main accents of the melody are around the note C, so it sort of feels like that is the centre, but if you try playing around with this melody you can make it feel like the centre is anywhere. If you play a whole tone scale starting on C, the notes are C – D – E – F# – G# – A#. Any whole tone scale built from any position in this scale will have all the same notes in it, as it is the same in every direction (it is just tones after all…). So in a way there are really only two different whole tone scales: One with the six notes C – D – E – F# – G# – A# and one with the other six notes Db – Eb – F – G – A – B.

As most of the music in Ocarina of Time is modal, the use of the whole tone scale in this piece really makes it stand out. It is so harmonically different to almost every other piece in the game. To me this really highlights the importance of knowing different musical devices, and knowing how to use them. Variety is probably the most important aspect of good composing.

If you are a composer and you haven’t tried writing any whole tone music, you should give it a try. It’s a real challenge! It will definitely test the limits of your musical imagination. If you end up having to compose some mysterious or dream-like music, you never know, the whole tone scale might come in useful.

If you enjoyed this lesson, make sure you check out our other blogs, and stay tuned for further lessons. If you’re serious about furthering your knowledge and your career in music, check out our Postgraduate and Premium courses on our website and see which ones are suitable for you. We’re always happy to help, so send us an email at contact@thinkspace.ac.uk with any questions and we’ll get back to you.