Jake Few is a multi-instrumentalist and course producer at ThinkSpace Education. He has worked as a musical director and composer for an Off West End musical theatre production and holds a degree in Music Composition and Technology for Film and Games. Jake is also a contributor to our new Practical Harmony 2 course, available now on introductory offer.

It’s easy to get stuck writing simple 4-chord progressions. Don’t worry, we get it. The temptation of a simple C to F to G is a powerful one. However, there are ways to spice up those kinds of progressions, and that’s what we’ll show you here.

Some of the most memorable songs and compositions have very simple chords, and are great because of their simplicity. But, simplicity won’t always do the job, especially if you’re repeating sections! Learning how to explore new harmonic territory, and present the same musical information in a variety of interesting ways, is often one of the signs of a great musician or composer.

In this blog, we’re going to take a short chord progression and spice it up using 2 different techniques: a secondary dominant, and a tritone substitution.

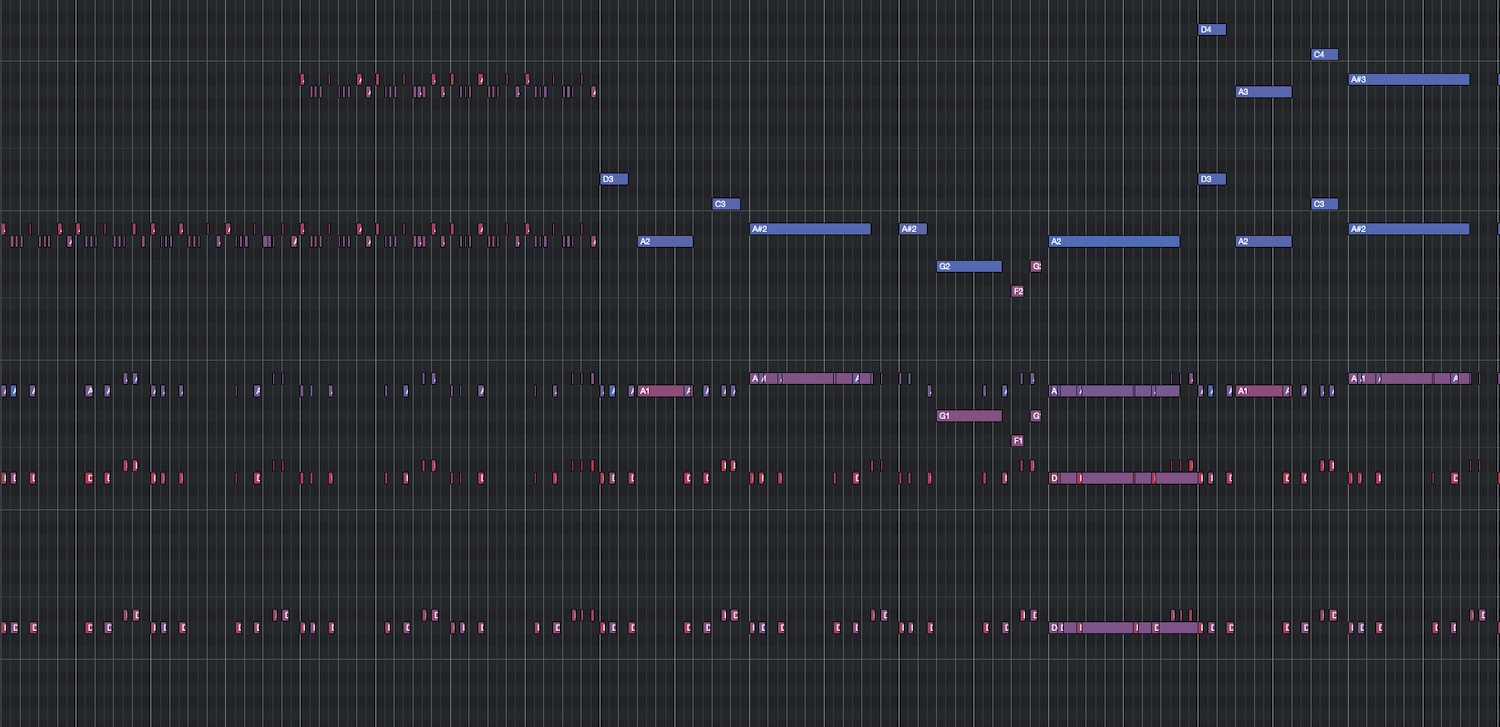

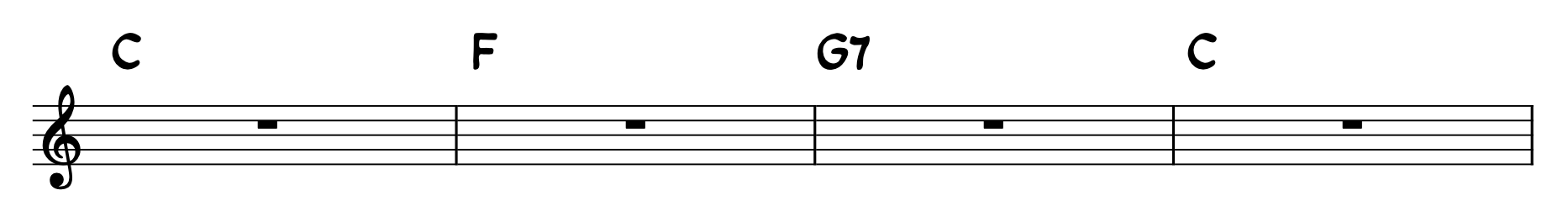

Those might sound rather daunting if you are unfamiliar with them, but fear not! It really is quite simple to understand. This is the chord progression we’ll be upgrading:

It doesn’t get much simpler than that! We’re going to insert new passing chords or replace some altogether.

What Are Secondary Dominants?

The term dominant gets thrown around constantly, but it refers to a few different things.

- It is the name of the 5th scale degree (G in the key of C major).

- It describes the function of a chord; a chord with a dominant function resolves to a tonic chord.

- It also refers to a ‘dominant 7th’ chord, meaning a triad with a minor 7th, typically built on the 5th scale degree (hence its name) but not always.

In C major, a G7 chord fits all three of these descriptions. It is the primary dominant.

A secondary dominant chord is a dominant 7th chord that resolves to somewhere other than the tonic. For example, a D7 chord in the key of C is a secondary dominant, because it resolves down a perfect 5th to G major.

A conventional definition of secondary dominant is a dominant 7th chord that resolves to a chord that is in the home key. This means you have five secondary dominants in any major key.

Secondary Dominants in C major:

C7 resolves to F major

D7 resolves to G major

E7 resolves to A minor

A7 resolves to D minor

B7 resolves to E minor

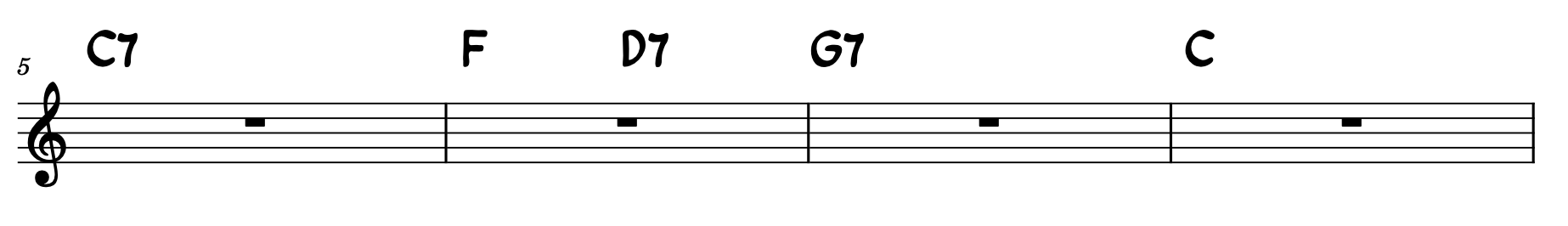

So what does this mean for our chord progression? Well, we can simply add a 7th chord in place of the C major, resolving to F major. Or, insert a D7 passing chord before the G major chord. Why don’t we do both?

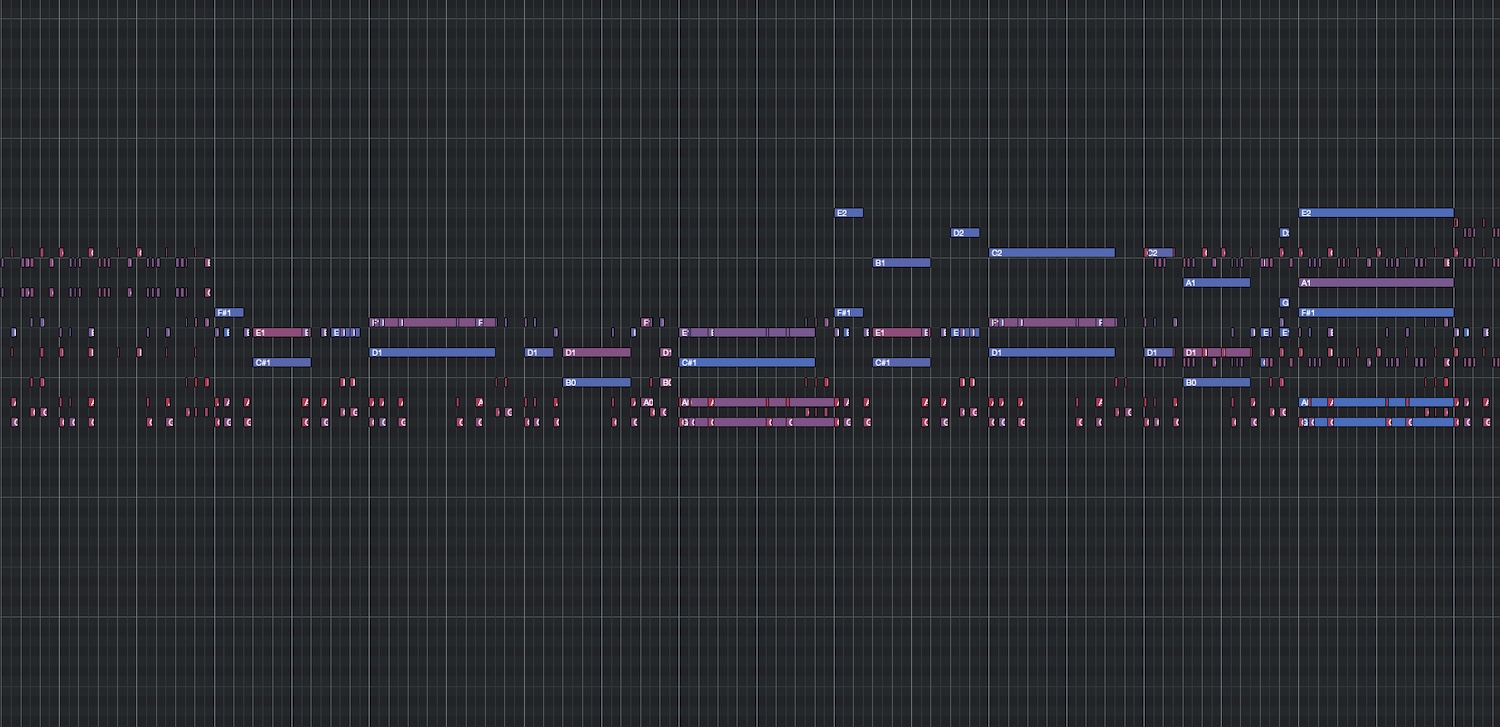

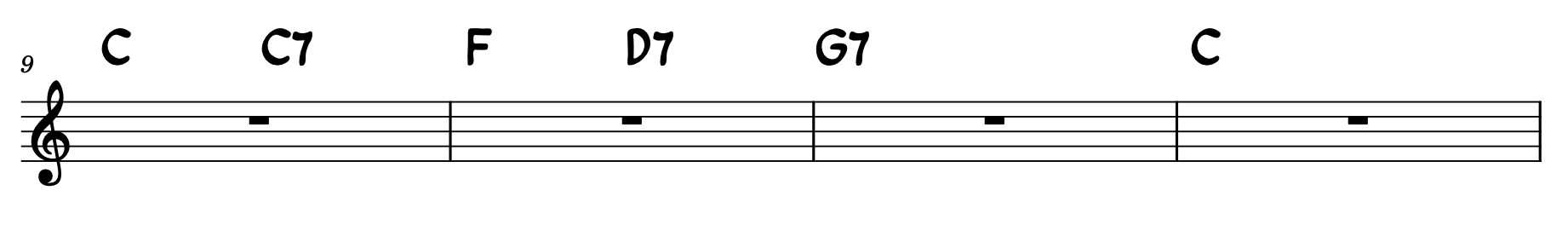

So our chord progression is now:

But first, why don’t we leave the C major for half a bar before moving to the C7? Now you can hear the clear movement between the C and C7.

What do you think? The use of a secondary dominant gives a clear signpost for where your chord is likely to go next. Using these secondary dominants, and all of our strong familiarity with that V7 to I movement, we can guide the listener's ear so our chords feel a little less randomly selected, and a little more directional.

What Are Tritone Substitutions?

As the name suggests, a tritone substitution is when a chord is substituted for a different chord a tritone away. This typically happens to a dominant 7th chord. So in C major, the G7 chord could be substituted for D♭7, as a tritone above G is D♭.

But why does this work? Look at how a G7 is constructed compared to the D♭7.

G - B - D - F

D♭ - F - A♭ - C♭ (B)

The two notes in a G7 chord that hold a lot of harmonic power are the 3rd (the B, being the leading note back up to the C tonic), and the 7th (the F, resolving nicely down to the 3rd of our tonic, E).

Both of these notes appear in our tritone substitution too, although the function is swapped - the 7th in G7 is the 3rd in D♭, and vice versa. This gives us a similar harmonic pull back to the tonic, but from a very different place.

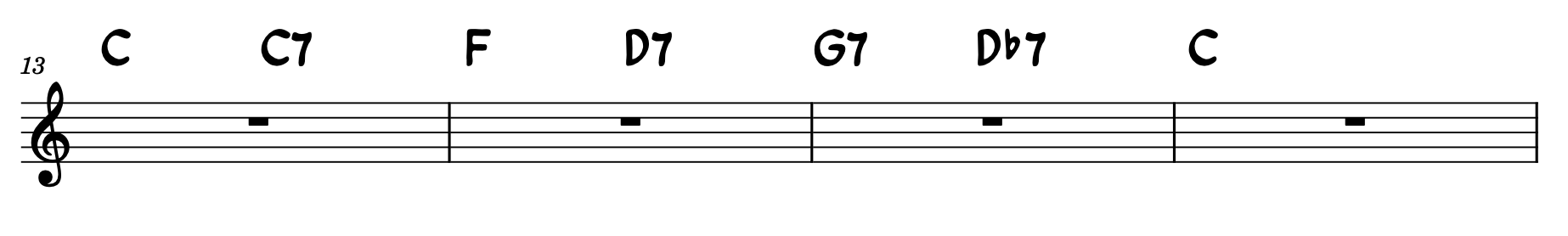

So, we could entirely replace our G7 chord in our chord progression with the tritone substitution, but I’m not a fan of that as you lose the direction already set up by the D7 secondary dominant. So, like we’ve done with those other chords, let’s put it in as a passing chord back to the tonic.

Can you see how far we’ve come? We’ve only used two simple techniques, and without much crafting going into them, at that!

Some final tips for you:

- These techniques can be a nice way to breathe fresh life into a chord progression the listener has already heard. You may want to use them right from the start of your piece, but they can be used as developments of previously established chord progressions.

- Tritone substitutions don’t just have to be used on the dominant. They work quite nicely in place of, or as well as, secondary dominants too. For example, splitting our secondary dominant in half and playing it a tritone higher to lead to the dominant: D7 - G♯7, G7 - D♭7, C.

- Don’t think of these as just ‘jazz’ techniques. You find them in all music - film and game music, acoustic ballads, jazz fusion, and so on. Certain genres do favour particular harmonic techniques, but they by no means own those techniques.

If you want to learn more about this, check out Practical Harmony 2. We’ve dedicated an entire module to show you how to get the most out of secondary dominants, including borrowed chords, modes, extensions and alterations, complex jazz theory, and how to arrange your chords over whole pieces of music.

No more fumbling in the dark when it comes to interesting chord choices - we’ve packaged it all up for you, so just pick and choose your favourite sounds and learn the theory by doing, not by reading. Well, perhaps a bit of reading…