There’s a lot to learn about music from Ocarina of Time. In the first part of this series, we will be looking at modes.

The music in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time is not just fantastic, it’s also integral to the storyline. Luckily they had maestro Koji Kondo at the helm, the man responsible for the Super Mario Bros. music, so they were in good hands.

Let me just briefly explain why the music is so important, for those of you who haven’t played the game (which you really should have by now). In it, the player has to learn a repertoire of magical songs on the eponymous ocarina to be performed at appropriate times throughout the game (the Song of Storms makes it rain, the Sun’s Song makes the sun set or rise, the Bolero of Fire warps you to the fire temple etc). There are 12 songs in total, but only 5 buttons to play them with. This means that Kondo had to be pretty creative to avoid repetition and make all the music unique. For this, he harnessed the awesome power of the modes.

What is a mode? A major scale is a specific pattern of tones and semitones. To move one semitone is to move to the nearest note (C to C# for example), and a tone is two semitones (C to D). Starting from the root note of your major scale, the pattern of ascending intervals is T-T-S-T-T-T-S. If one was to start with C on a piano, this pattern of tones and semitones would give you all the white notes, with the semitones between E and F, and between B and C. Imagine you were to keep that specific pattern of tones and semitones, but begin and end on a different note within that pattern. The order of the intervals will be different and so will the sound it produces. That’s what a modal scale is: a scale built from one of the permutations of this specific pattern of tones and semitones. There are seven tones and semitones in this pattern, so there are seven modes:

Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, Locrian.

Exotic sounding right? The modes all have Greek names, as they were rather fond of them (in fact the earliest known complete song is a little Greek ditty found on a tombstone called the ‘Seikilos Epitaph’, in the Mixolydian mode). They’re also sometimes called the church modes because of their use in early church music. Here’s a neat little mnemonic to help you remember the order:

I Don’t Particularly Like Modes A Lot.

(I know that there are two Ls so you may confuse lydian with locrian, but there’s no way around it, you’ll just have to learn which way round they go!)

So, the major scale pattern is T-T-S-T-T-T-S. The Dorian mode begins on the second position of this pattern. This means that the pattern of intervals in the Dorian mode is T-S-T-T-T-S-T. The Phrygian mode begins on the third position, so this means the pattern is S-T-T-T-S-T-T. Easy, right? The pattern just loops round from a different starting point (Ionian and Aeolian are just the modal names for the major and minor scale, by the way). Try playing around with these modes at home so you can get used to how they sound.

So how does this apply to Ocarina of Time? As previously said, there are only five notes you can play on the ocarina, but 12 songs. But by making the tunes centre around different notes, and therefore be in different modes, Koji Kondo has created great melodic diversity. Let’s look in detail at some of the tunes.

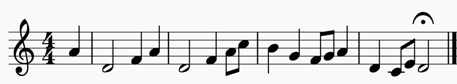

Song of Time

This rather holy-sounding song is in the Dorian mode. Whilst this pattern of intervals is T-S-T-T-T-S-T, it’s best to think about the Dorian mode as a natural minor scale with a major six. The major six is what makes the Dorian sound different to the minor scale. It also makes it sound a little less mournful, so it can be good to use it if you want your music to be a little bit between major and minor, but more towards minor.

(Just in case some of you were thinking “There’s more than five different notes in that melody”, in the game you only have to play the opening notes of the tune and the rest is automatically played)

Until we get to the major sixth, the B natural in the third bar, you wouldn’t be able to tell this was Dorian instead of minor (in D minor it would be B flat), as all the other notes are the same. Remember, it’s the major sixth that gives the Dorian mode its distinct flavour. If you want a melody to have the Dorian flavour, make sure the sixth is in there. Otherwise it’s just a minor scale.

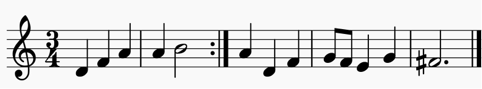

Serenade of Water

Here is another tune in the Dorian mode. Like the Song of Time, the main melody is based around a D minor arpeggio. The difference is that after the minor arpeggio it goes straight to the B natural, the major sixth, so the Dorian nature of the melody is quickly established.

‘Hey, why is there an F sharp at the end? If we are in the Dorian mode, the third should be a minor, not a major.’

Sometimes the end chord of a tune in a minor key (Dorian is a minor mode) lands on a major triad on the tonic instead of a minor (the tonic is the root note of the key or mode). The F sharp at the end of this piece is the third of a D major chord. This is a compositional device known as ‘Tierce de Picardie’, or sometimes more colloquially as a ‘Picardy third’. It’s a way of making your minor music not end on such a downer. This is commonly found in Baroque music, but this was more because they felt the minor chord was not strong enough to end on. This happens a lot in Bach’s music.

You may have heard the Dorian mode used in more popular music too. The Beatles’ song Eleanor Rigby moves between the minor scale and Dorian mode. Having melodies in your music change between similar modes is a great way of creating variety. Try transposing some melodies, your own or other composers’, in to different modes and listen to the difference.

Saria’s Song

We’re moving away from the sombre domain of the Dorian in to the wacky world of the Lydian mode. What makes it so wacky? Well, the Lydian mode is the only one that has no perfect fourth, but instead an augmented fourth. This interval also known as a Tritone, as it is the equivalent distance of three adjacent tones. The Locrian mode also has a tritone from the root, but that is because of its diminished fifth, not augmented fourth.

What is so wacky about the tritone? It’s a dissonant interval, both melodically and harmonically, so much so that in the past it was known as the ‘Diabolus in Musica’, the Devil in Music, for it’s supposedly evil sound. However, tastes change, and it isn’t so un-palatable to modern listeners anymore. Depending on the context in which it is used, it can sound quite playful (in a slightly sinister way). The theme tune to The Simpsons uses the Lydian mode to create that distinctive zany sound.

Where the Dorian mode is like a minor scale with a major sixth, the Lydian mode is like a major scale with an augmented fourth. The augmented fourth is what gives the Lydian its distinctive flavour. Starting on F, the augmented fourth is a B natural (a perfect fourth, like one would find in an F major scale, would be a B flat).

In Saria’s Song, the melody starts on the root note F and moves to the augmented fourth through a passing note, which makes it less melodically dissonant, but not completely so. It has a playful, childlike quality to it, but still has that slightly dark tone. It sounds very different to how it would be if it was just in F major. Try playing it with the B flat instead of the B natural and you’ll hear the difference.

There’s a lot more to be learned from Sensei Kondo’s work, but I’m afraid that will have to wait until next time! If you enjoyed this lesson, make sure you check out our other blogs, and stay tuned for further lessons. If you’re serious about furthering your knowledge and your career in music, check out our Postgraduate and Premium courses on our website and see which ones are suitable for you. We’re always happy to help, so send us an email at contact@thinkspace.ac.uk with any questions and we’ll get back to you.