Every great score tells a story — but how do you make your music do the same? Robert Rodriguez explores how to create music that feels cohesive, purposeful, and true to the world on screen.

Robert Rodriguez is a composer, orchestrator, and educator who’s collaborated with leading sample developers like EastWest Sounds, Cinesamples, and Westwood Instruments. He's also a tutor on our Orchestral Composition Bootcamp, an 8-week programme of live webinars and feedback with pro composers. Sign up here.

“Story” has become a bit of a buzzword.

Every big-name composer will tell you it’s the key to every project.

Zimmer, Giacchino, Powell…interview after interview, their advice is largely the same: focus on the story.

But what does that mean in practice? How do we actually write music that feels narratively cohesive? Where do we begin?

Musical storytelling is about scoring the why behind a scene – whose head we’re in, what isn’t being said out loud, and what this world actually sounds like. How can we translate the filmmaker’s vision into a unified world and a cohesive set of ideas that move the narrative forward?

Always start with your director’s vision.

When I got my first few gigs, I wanted to prove myself as a composer. So I’d try and create a masterpiece right out of the gate. But the reality was that I’d put so much effort into trying to come up with as close to a final draft as possible, that I was missing the most important part…understanding the message the director was trying to share! I’d just write cue by cue without seeing the overarching picture.

But now, before I even touch my keyboard or open my DAW, I want a clear understanding of the director’s vision. Why this project, why now, what do they want the audience to feel or question?

I love these initial conversations because you get a glimpse of the personal stake your collaborators have in this project. Now, it might not always be possible to get a long one to one sit down with the director. Honestly, your first composing gig might even just be working on a 30 second advert without much of a “story.”

But just taking the time to dive a bit deeper into their why in addition to the brief could make all the difference. The goal here is to find a moment or feeling that you can personally latch on to!

Once you feel like you have a good understanding of the direction of the story, this is the time to just explore. Don’t commit to anything yet but allow ideas to influence more ideas. Not everything is going to work, not everything is going to be “good”…and that’s okay.

This is your chance to just define the palette of sounds for this world that you’re helping create. As artists, we tend to be precious with our music to the point where we don’t want to share our work until it feels ready.

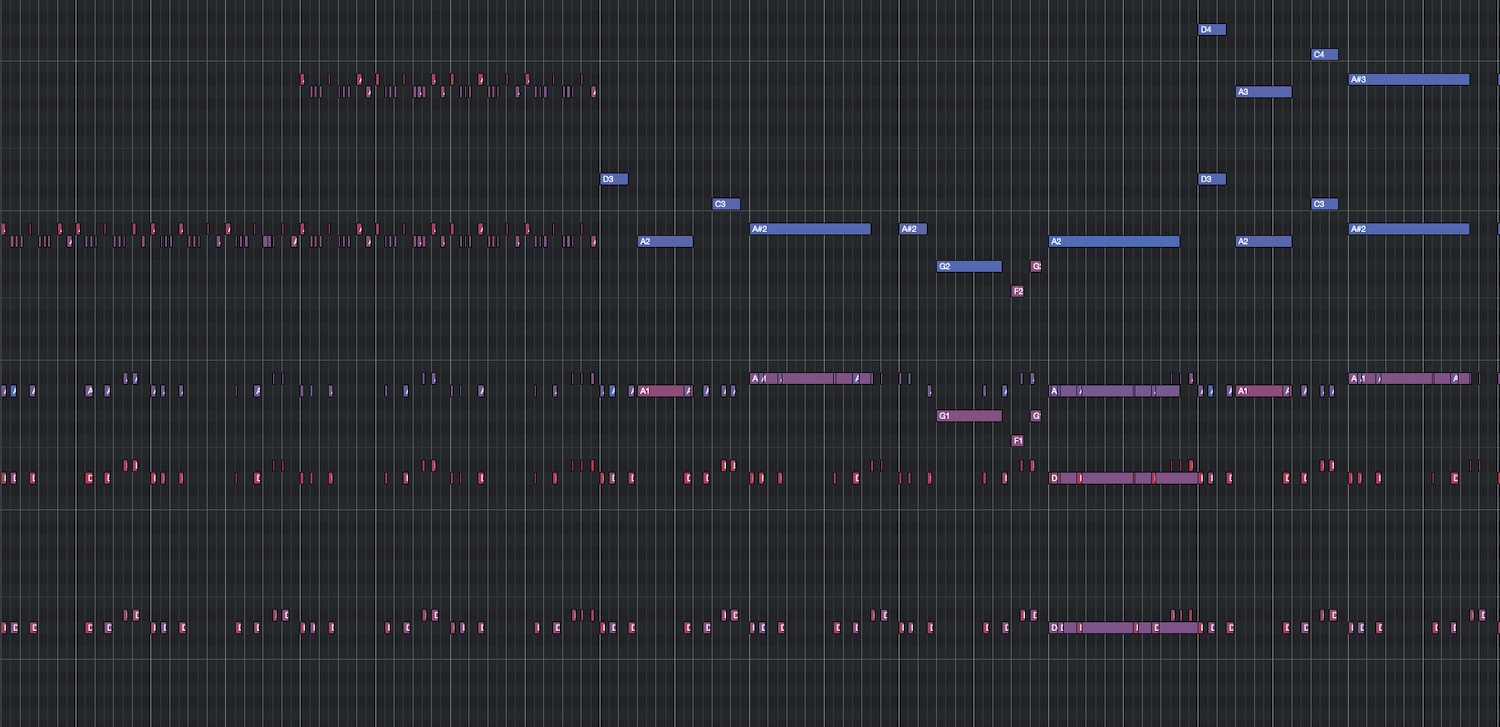

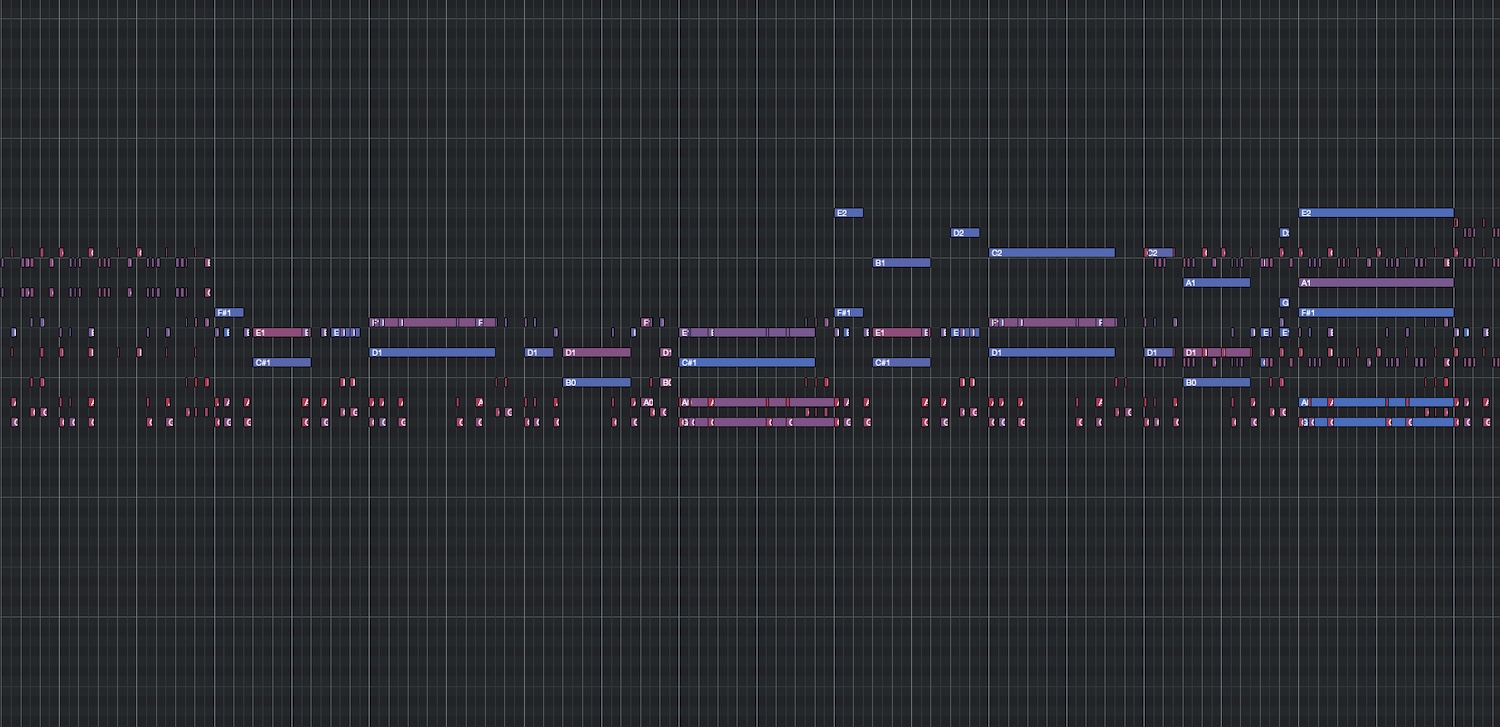

But now is the time to share those drafts with your collaborators to see which instruments are working, which to avoid, which ideas stick. Out of that exploration, a palette starts to reveal itself…specific timbres, textures, motifs and rhythms.

Take Ludwig Göransson’s The Mandalorian score for example. It’s far from John Williams’ original Star Wars material and yet it works so well for the story of a space western gunslinger. Göransson found his sound for this particular world through synths, guitars, drums, piano, and of course the now iconic bass recorder melody.

If you were in his shoes, you might want to ask yourself questions like: What does this particular Mandalorian sound like? What does the relationship between the Mandalorian and Grogu sound like? What about the sound of the spaceship or a specific planet? And though Göransson completely redefined and expanded on the sound of Star Wars, he was still able to pay homage to the original score through his own version of an orchestral fanfare.

Once the world feels consistent, I tend to start thinking about themes and leitmotifs…just a small, recognizable idea. Maybe it’s an interval, a contour, a tiny rhythmic movement. The key is to think of themes as adaptable and ever-changing…never truly set in stone.

I think of thematic writing as a web, not a straight line.

You start with a main idea, maybe something like a character theme. When that character faces loss, the idea branches: you shift interval emphasis, darken the harmony, pass it on to a solo, fragile voice. When they’re triumphant, another branch opens: brighter intervals, clearer harmony, wider voicings, larger instrumentation. Regardless of the change, the core idea is recognizable for your audience!

And Siddhartha Khosla’s work on Only Murders in the Building is a great example of this. Anyone who’s seen the show likely has had the music stuck in their heads for days! The main title theme anchors the series, but we hear variations of it in nearly every episode!

In intimate or pensive moments you might hear it as a high, delicate piano. During an investigation, it may shift to a more curious woodwind choir. There are times when the melody steps back while the rhythmic cello outlines the chords, creating a sense of urgency. And during the episode cliffhangers (often moments of discovery), a Baroque-like ensemble takes over with string ostinatos, arpeggios, a sweeping melody along with a grand orchestration.

Five seasons in, the identity is instantly recognizable yet still feels new because of Khosla’s effective use of thematic variations. It’s familiar to the audience and faithful to the story of three amateur podcast investigators and their evolving relationships.

Ultimately, there’s no single “right” way to tell a story in music…no perfect chord progression or melody. What matters is getting close to the film’s emotions, its world, its relationships, and the scene’s why. As the core idea repeats, recognition for it builds. Then an octave jump might feel hopeful, a thinned texture may feel fragile, a rhythmic variation increases momentum. That’s how you can naturally weave story into your music!